The Criminal Mastermind of Baker Street Read online

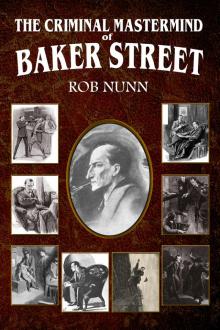

The Criminal Mastermind of Baker Street

Rob Nunn

Published in the UK by

MX Publishing

335 Princess Park Manor, Royal Drive,

London, N11 3GX

www.mxpublishing.co.uk

Digital edition converted and distributed by

Andrews UK Limited

www.andrewsuk.com

© Copyright 2017 Rob Nunn

The right of Rob Nunn to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998.

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without express prior written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted except with express prior written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person who commits any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damage.

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of MX Publishing or Andrews UK Limited.

Cover design by Brian Belanger

Introduction

In “The Adventure of the Speckled Band,” Sherlock Holmes said,” when a clever man turns his brains to crime it is the worst of all.” What if one of the cleverest men in London had in fact turned his brains to crime instead of detection? Sherlock Holmes believed that crime was common, but logic rare. How would Victorian London have looked if Holmes had decided to combine the common crime element in London with his superior logic to create a great criminal empire? Criminal organizations have operated under a less impressive mind many times. How would Doctor Watson fit into a world where Sherlock Holmes was a criminal mastermind? Would Professor Moriarty be Holmes’ friend of foe? If Sherlock Holmes decided to pursue crime instead of thwarting it, what would that London look like?

The following book is an examination into this hypothetical situation. All of the original players are still here: Doctor Watson, Mycroft Holmes, Scotland Yard, and the others. Using William Baring-Gould’s chronology of the Sherlock Holmes cases, I have attempted to reimagine how all of events from the Canon would look if Sherlock Holmes were not trying to prevent these crimes, but were behind many of the crimes himself. Some of the original cases would not be of any interest to him, sometimes Holmes’ involvement would remain similar to how he behaved as a consulting detective, and sometimes his responses to events would be wildly different. Let us investigate how Sherlock Holmes, Doctor Watson, and London would have been affected by Holmes’ decision to become the criminal mastermind of Baker Street.

Chapter 1: Begin at the Beginning

“Dr. Watson, meet Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” young Stamford said as he introduced the two strangers in the laboratory at St. Bart’s Hospital one January day in 1881.

The young man looked up from his chemical research and greeted them. “How are you?” Sherlock Holmes asked cordially, gripping Watson’s hand with strength that surprised the doctor. His sharp and piercing eyes took in the doctor at a glance. “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.”

Suspicious, Watson asked the tall, gaunt man, “How on earth did you know that?”

A smile crossed Holmes’ thin, eager face. “When I saw you, I thought ‘Here is a gentleman of a medical type, but with the air of a military man. Clearly an army doctor then. He has just come from the tropics, for his face is dark, and that is not the natural tint of his skin, for his wrists are fair. He has undergone hardship and sickness, as his haggard face says clearly. His left arm has been injured. He holds it in a stiff and unnatural manner. Where in the tropics could an English army doctor have much hardship and got his arm wounded? Clearly in Afghanistan.’”

“Interesting,” Watson remarked.

“Never mind. The whole train of thought did not occupy a second,” remarked Sherlock Holmes, pricking a finger on one of his hands that were blotted with ink and stained with chemicals to draw a drop of blood and then placing a small piece of plaster over the prick. “I have to be careful,” he continued, noting Watson’s look, “for I dabble with poisons a good deal.”

“We came here on business,” said Stamford, sitting down on a three-legged stool. “My friend here wants to take diggings and is looking for employment, but is slightly embittered at how the great cesspool of London is treating a wounded war veteran. I thought that I had better bring you together.”

“A veteran,” Holmes mused. “You are not of active duty.”

“No,” Watson continued. “I was an assistant surgeon for the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers, but I was struck in the shoulder by a Jezail bullet. After regaining my strength at the base hospital, I suffered an attack of enteric fever, leaving me laid up until I was discharged and sent back to here to London where I have no kith or kin. I mentioned all this to Stamford over lunch and he said that you seem to know of most things in London and might be able to point me in the direction of employment and a place to call home.”

Stamford was correct that Holmes knew of most things in London. Sherlock Holmes loved to lie in the very center of the five millions of people in London, with his filaments stretching out and running through the city, a city he considered his city. Holmes was attentive to every little rumor, suspicion or opportunity that came his way, and this strongly built doctor who had just been introduced to him presented a definite opportunity.

“I might know something about employment in a few days, but as for lodgings, you may start and end here,” Holmes stated. “I have been looking for someone to go halves on a suite in Baker Street. You don’t mind strong tobacco, I hope?”

Happily surprised at the possibility of finding decent lodgings, Watson answered, “I always smoke ‘ships’ myself.”

“That’s good enough. I generally have chemicals about, and occasionally do experiments. Would that annoy you?”

“By no means.”

“Let me see - what are my other shortcomings. I get in the dumps at times, and don’t open my mouth for days on end. You must not think I am sulky when I do that. Just let me alone, and I’ll soon be right. What have you to confess now? It’s just as well for two fellows to know the worst of one another before they begin to live together.”

Watson laughed at the cross-examination. “I object to rows, because my nerves are shaken, and I get up at all sorts of ungodly hours, and I am extremely lazy. I have another set of vices when I’m well, but those are the principal ones at present.”

Seeing beyond Watson’s initial assessment of himself, Holmes asked, “Do you include violin playing in your category of rows?”

“It depends on the player. A well-played violin is a treat for the gods - a badly-played one...”

“Oh, that’s all right,” Holmes laughed. “I think we may consider the thing as settled - that is, if the rooms are agreeable to you. Call here at noon tomorrow, and we’ll go together and settle everything.”

“All right - noon exactly,” said Watson, shaking Holmes’ hand.

Watson and Stamford left Sherlock Holmes working among his chemicals. Once out of the room, Watson turned to Stamford, “Was he really able to deduce so quickly that I had come from Afghanistan? Did you tell him about me?”

Stamford smiled. “No, no. That’s just his little peculiarity. A good many people have wanted t

o know how he finds things out. You mustn’t blame me if you don’t get on with him.”

Watson stopped and looked hard at his companion. “It seems to me, Stamford, that you have some reason for washing your hands of the matter. What is it? Don’t be so mealy-mouthed about it.”

“Nothing so serious,” Stamford replied. “It is not easy to express the inexpressible. Holmes is a little too scientific for most people’s tastes - some would say that it approaches cold-bloodedness. He appears to have a passion for definite and exact knowledge.”

“Very right too.”

“Yes, but it may be pushed to excess. When it comes to beating the subjects in the dissecting rooms with a stick, it is certainly taking rather a bizarre shape.”

“Beating the subjects!” Watson ejaculated.

“Yes, to verify how far bruises may be produced after death. I saw him at it with my own eyes. But as far as I know, he is a decent fellow enough.”

“After my time in Afghanistan, I don’t find myself too picky of company. He is a medical student, I suppose?” Watson asked.

“No - I have no idea what is his actual employ. I believe he is well up in anatomy, and he is a first-class chemist; but, as far as I know, he has never taken any systematic medical classes. His studies are very desultory and eccentric, but he has amassed a lot of out-of-the-way knowledge which would astonish professors. At times, he seems to be a walking calendar of crime, always talking of police news of the past. He is not a man that is easy to draw out, though he can be communicative enough when the fancy seizes him.”

“Oh! A mystery is it? This is very piquant. I am much obliged to you for bringing us together. The proper study of mankind is man, you know.”

“You must study him, then,” Stamford said, as he bade Watson goodbye. “You’ll find him a knotty problem, though. I’ll wager he learns more about you than you about him.”

Holmes and Watson met at noon the next day and inspected the rooms at 221B Baker Street. They consisted of a couple of comfortable bedrooms and a single large airy sitting-room, cheerfully furnished, and illuminated by two broad windows. The two men found the rooms and the rates so desirable that they closed the deal on the spot.

During their first few weeks together, Watson made good on his word to Stamford that he would make a study of Sherlock Holmes. Watson noted that Holmes would sometimes spend his days at the chemical laboratory, sometimes in the dissecting room, and occasionally in long walks, which appeared to take him to the lowest portions of the city. His zeal for certain studies was remarkable, and within eccentric limits, his knowledge was so extraordinarily ample and minute that his observations would astound Watson.

While Watson was making a study of Holmes, Holmes was of course studying Watson in turn. After their first week together, Holmes knew that Watson was a solid and reliable man and felt comfortable enough to receive callers in their new home. Watson found himself confused by Holmes’ many acquaintances from all different classes of society. One morning, a fashionably dressed young girl called and stayed for a half hour. Later that day, a gray-headed, seedy visitor came by. Other visitors included an old, white-haired gentleman, a slipshod elderly woman and a railway porter in his velveteen uniform. Anytime one of these visitors came by, Holmes would beg for use of the sitting-room. He would apologize to Watson for the inconvenience, telling him that he had to use that room as a place of business and those people were his clients. Watson simply took himself to another room and never seemed to be bothered by these clients, no matter their social class, which pleased Holmes and solidified his judgment of the doctor’s character.

Two months after they had moved into Baker Street, Watson rose early one morning and found Holmes already seated at the breakfast table, reading a French book on graphology. Watson picked up a magazine and his eyes fell upon an article titled The Book of Life. As he read the article, he became more and more astounded by the claims in it. The author of the article claimed that by a momentary expression, a twitch of a muscle or a glance of an eye, to fathom a man’s innermost thought. Deceit, according to him, was impossible in the case of one trained to observation and analysis. The article went on to proclaim that the practitioner of deduction could meet a fellow mortal, learn at a glance to distinguish the history of the man and the profession to which he belongs.

“What ineffable twaddle!” Watson cried, slapping the magazine down on the table. “I’ve never read such rubbish in my life.”

“What is it?” Sherlock Holmes asked innocently.

“This article. I see that you have read it since you have marked it. I don’t deny that it is smartly written. It irritates me though. It is evidently the theory of some armchair lounger who evolves all these neat little paradoxes in the seclusion of his own study. It is not practical. I should like to see him clapped down in a third-class carriage on the Underground, and asked to give the trades of all his fellow-travelers. I would lay a thousand to one against him.”

“You would lose your money,” Holmes remarked. “As for the article, I wrote it myself.”

“You!”

“Yes; I have a turn both for observation and for deduction. The theories which I have expressed there, and which appear to you to be so chimerical, are really extremely practical - so practical that I depend upon them for my bread and cheese.”

“And how?” Watson asked.

After a methodical study of John Watson, Holmes had decided that he was an intelligent, trustworthy and adventurous man whose time in Afghanistan and return to London had allowed his morals to be less rigid than many other Victorian gentlemen. Now that Holmes felt confident in his assessment of the former army doctor, he had had this article published to spark such a conversation, to make it seem as though Holmes’ line of work had come up in conversation organically.

“Well, I have a trade of my own. Yes, it has been done before, but not to the level of which I aspire. To the average person, my persona is that of a gentleman with eccentric interests who then turns those studies into monographs and articles. I have published writings on subjects as far-ranging as differences in cigar ashes to the origin of tattoo marks. But in reality, my specialty is planning and executing crimes so perfect that they are untraceable. You might call me a consulting criminal.”

Surprised, Watson sat back in his chair.

“Before you object, Doctor, my plans are, almost without exception, devoid of violence. What would be served by a circle of misery, violence and fear? Nothing. I take the view that a when a man embarks upon a crime, he is morally guilty of any other crime which may spring from it. You see, I strive to elevate criminal activity to a gentlemanly fashion. Society can never do away with crime completely, so why not civilize and organize the practice? My methods will greatly reduce dangerous criminals acting with malice towards their victims, for violence does recoil upon the violent. I also strive to eliminate poorly planned crimes resulting in harm coming to people when it can be avoided. You said that Stamford called me a walking calendar of crime, and he had no idea how close to the truth he really was. I have made a study of past crimes, and endeavored to learn from them. Take, for example, the Worthington bank robbery in 1875. The gang’s bumbling led to one murder and five prison terms. It was only luck that a guard was not present during the robbery, or surely more blood would have been shed. If I had a hand in the planning of that case, no one would have been harmed, hanged or even caught.

“Look out the window to the fog that permeates London,” Holmes continued. “A thief or murderer could roam London on such a day as the tiger does the jungle, unseen until he pounces and then he is evident only to the victim. But if there is a great, controlling force that oversaw all crime in London, petty thugs would know not to accost citizens, and that working under my tutelage would benefit them more than acting on their own ideals. But I am also happy to consult on other’s plans for a fee and to help thos

e in need. Those people you have seen in our rooms are my clients. They are mostly sent on by my private inquiry network of agents. They are all people who are in trouble about something, and want a little enlightening. I listen to their story, they listen to my comments, and then I pocket my fee.”

Intrigued, Watson asked, “Do you mean to say, that without leaving your room you can unravel some knot which other men can make nothing of, although they have seen every detail for themselves?”

“Quite so. I have a kind of intuition that way. Now and again, a case turns up which is a little more complex. Then I have to bustle about and see things with my own eyes. You see I have a lot of special knowledge which I apply to the problem, and which facilitates matters wonderfully. Those rules of deduction laid down in that article which aroused your scorn are invaluable to me in practical work. Observation with me is second nature, such as when I deduced that you had come from Afghanistan. This trait benefits my organization’s planning greatly.”

Watson sat quietly, and Holmes poured him a cup of tea from his favorite plantation in India.

“But how could you have created such a profession? And why has no one before you done so?” Watson questioned, stunned but intrigued.

“When I attended university, I realized how great my capabilities were. One afternoon, I was sharing my talent with my friend’s father, and he pointed me in my line of work. I had only thought of this as a hobby until that day.”

“And why did you never use your abilities to solve crimes instead of committing them?”

“I had intended to do so in my own capacity, and even helped Scotland Yard solve the Tarleton murders in ‘78, but when another university acquaintance hired me to solve a mystery at his estate, my course changed that day. His butler had solved an old, peculiar family ceremony that led to the finding of the ancient crown of the kings of England. The butler’s intellect solved what had gone unnoticed for generations, but in the end, he was undone and ultimately died because of poor planning on his part. I was able to solve the same problem, but the treasure was turned over to the one who had hired me.

The Criminal Mastermind of Baker Street

The Criminal Mastermind of Baker Street